Respiratory diseases are second only to problems affecting the musculoskeletal system when it comes to limiting the ability of a horse to perform to its maximum potential.

The respiratory system supplies oxygen to red blood cells and removes carbon dioxide from the blood. Without adequate oxygenation, working muscles and organs enter a state of anaerobic metabolism, resulting in a build-up of lactic acid that will ultimately limit performance.

Horses can only breathe through their nose and can only increase oxygenation to the lungs by boosting their respiratory rate and effort. Unlike humans, the lungs of horses have little ability to respond to training, thus the respiratory system is always working at its maximum.

Any obstructions in the system can restrict airflow. When horses exhale during exercise, around 90% of the resistance (obstruction) to air movement is in the airways of the head (i.e. the nostrils, nasal passages and larynx).

Conversely, when horses are inhaling, the majority of the resistance to air movement (55%) is in the airways within the lung, therefore lower airway diseases can also have a restrictive effect.

Lower airway diseases

Diseases involving the lower airway are common and may affect horses of any age or breed. Infectious diseases caused by viral or bacterial infections can occur sporadically, but also may occur as outbreaks. Other lower airway diseases may be related to environmental or management conditions.

Although we have moved through the winter months and horses will be increasing their pasture turnout time, exposure to dust and pollens is often a trigger factor for susceptible horses to develop chronic lower airway disease.

Like humans, a viral cold is a common cause of coughing or respiratory tract infection in horses. The movement of horses around the country to studs, competitions and events increases the spread of viral infections.

Equine Herpes Virus (EHV)

EHV4 is common in the equine population and can present with a cough and serous nasal discharge that may turn yellow and cloudy, indicating the presence of bacterial infection and fever.

As well as causing respiratory disease, EHV1 can also cause abortion in pregnant mares. In 2014, a neurological form of EHV1 was identified in the Waikato.

If horses develop a fever and neurological signs (recumbency, hind limb paresis etc), or spontaneous abortions occur in pregnant mares, then these animals need to be isolated immediately and veterinary advice sought.

Nasal swabs, or examination of aborted fetuses and placentas, can identify the disease.

Vaccination is key

Vaccines for both EHV1 and EHV4 are available and are recommended for horses undergoing intense training programmes and that are in contact with other horses, and in broodmares that are travelling to studs. Many stud farms require broodmares to be fully vaccinated for EHV1 prior to arriving.

Horse ‘Flu’

Outbreaks of equine influenza occasionally occur in horse populations and in naïve unvaccinated animals. They can result in considerable economic losses, as was demonstrated in the Australia outbreak in 2007.

The incubation period of the equine flu virus is short (1 to 3 days), with the virus affecting the upper respiratory tract and to a lesser extent the lungs. The clinical signs occur 3 to 5 days after exposure to the virus, with horses exhibiting a sudden onset of fever and serous nasal discharge.

Other clinical signs can include anorexia, depression and a dry, deep, non-productive cough. Exercise exacerbates the clinical signs and secondary bacterial infections may occur.

Horses are infectious and may shed the virus for a further 3 to 6 days after the last signs of illness are exhibited.

In young foals, influenza can produce signs of viral pneumonia which may lead to death within 48 hours. Fortunately, equine influenza is not present in NZ and is a notifiable disease.

Risks following viral respiratory disease

Secondary bacterial pneumonia and pleuropneumonia are potential complications that may follow viral respiratory disease in horses that have not been rested adequately before returning to training. Or, that have undergone stressful events such as long trailer rides.

Pericarditis (inflammation surrounding the heart), myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle) and heart arrhythmias can also occur.

Early signs of bacterial pneumonia are not always obvious, and a gurgling sound and depression, or reduced appetite, may be all that is noted.

As the disease progresses, horses may show moderate to severe signs of respiratory distress, anorexia, fever, discharge of nasal mucus/pus, and a deep productive cough.

Identifying bacterial pneumonia

- Blood tests can reveal changes in total white blood cell counts, indicating the presence of a bacterial infection. Increased acute-phase proteins can also help to identify a focus of inflammation and, in some cases, the severity.

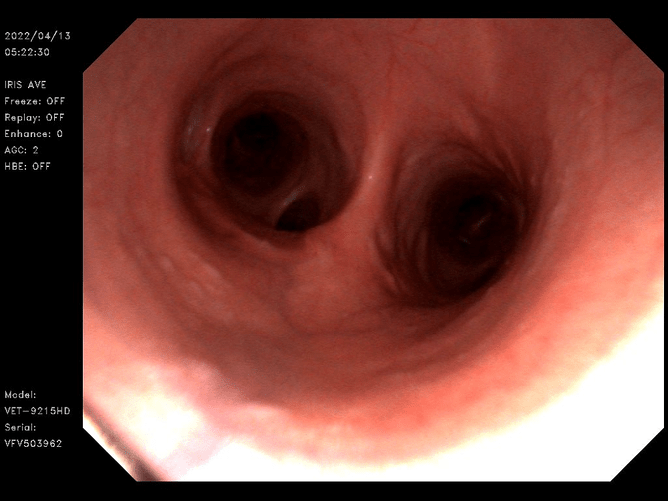

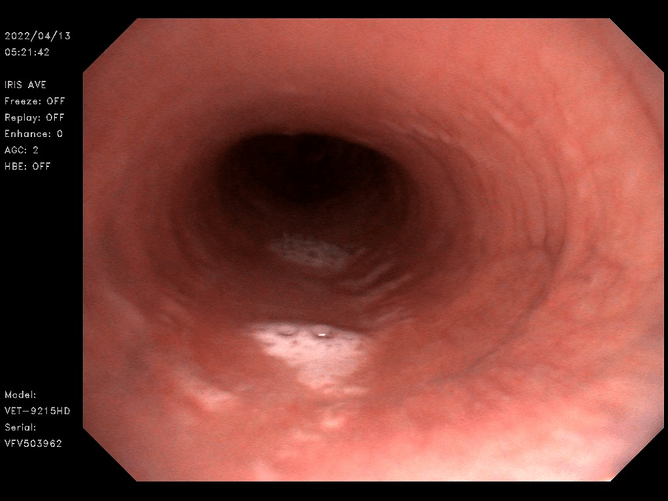

- Endoscopic evaluation of the lower respiratory tract. Obtaining a fluid sample can allow the bacteria to be cultured, and microscopic examination of the fluid helps to identify other infectious agents or abnormal cells.

- Ultrasonographic examination of the thorax, which is a non-invasive, simple procedure that can be used to identify areas of fluid or lung collapse.

- Radiography of the thorax is also a very useful imaging technique for identifying lung abscesses, masses, collapsed areas of lung, generalised lung disease, fluid and bronchial thickening or inflammation.

- Larger, fixed radiography units are required to obtain images of most adult horses, however, good images of foals or miniature breeds can be obtained using our smaller portable machines.

Treatment options

Treatment of bacterial pneumonia and pleuropneumonia involves targeted broad-spectrum antimicrobials, anti-inflammatories and rest.

In severe cases of pleuropneumonia, drainage of fluid or surgical debridement of large abscesses may be required. In many cases, antimicrobials should be administered for several weeks.

One to six month-old foals are susceptible to a particular bacterial pneumonia (Rhodococcus equi.), presenting with ill thrift and a failure to thrive compared to fellow peers. This is followed by mild to moderate signs of respiratory distress.

The development of lung abscesses is common, and treatment involves long term administration of particular families of antimicrobials.

Environmentally-driven diseases

Recurrent airway obstruction (RAO), chronic obstructive airway disease (COPD), heaves or ‘Equine Asthma’ are all terms used to describe non-infectious lower airway disease linked to environmental exposure of dust and pollen.

Generally, RAO occurs in older horses (over 14 years old) and can affect horses of all breeds. In younger horses, a similar syndrome known as Inflammatory Airway Disease (IAD) can be observed.In both RAO and IAD, there is an increased production of mucous and inflammatory cells, combined with the constriction of lower bronchi, that occurs as a response to allergens within the environment. The end result is obstruction of the lower airways, resulting in reduced airflow.

Signs to watch for:

- A dry, non-productive cough

- Possible signs of exercise intolerance

- Mild to moderate signs of respiratory distress

Endoscopic examination of the lower respiratory tract frequently reveals moderate quantities of cloudy white fluid within the lower trachea. Definitive diagnosis requires collection of a sample of the fluid from the trachea, and by taking a sample of cells from the bronchi and alveoli.

Treatment is based on removing the allergens from the environment, such as dusty bedding and feed stuffs. Soaking hay or feeding haylage and using dust-free bedding, such as coarse shavings, cut cardboard or peat moss, can substantially reduce the amount of dust in the horse's local environment.

It’s important to remember that the horse's entire stable area is part of its breathing space and should be kept as dust free as possible.

In affected horses, clinical signs frequently improve following removal of dust and antigens from the environment.

Management of these horses involves stabling the horse during the day when pasture pollen levels are at their highest. In younger animals (particularly 2-3 year old horses in training), inflammatory IAD can develop.

Many of these horses have a chronic cough and a history of poor performance. The condition is generally transient, and improves with increased field turnout; however, avoidance of undue stress is advised as secondary bacterial infections may develop.

IAD represents the most common form of respiratory disease that we encounter in our young race horses, and in some cases could lead to the development of Exercise Induced Pulmonary Haemorrhage (EIPH) or ‘bleeding’ during a race. Administration of immune stimulants such as levamisole or Equimune IV helps to improve the animal’s local immune response.

Summary

Lower airway inflammation and diseases are commonly encountered in the horse population. Although many diseases can be managed effectively with rest and environmental management, bacterial infections can potentially be life threatening. Severe recurrent airway obstruction can also limit performance.

To reduce performance-limiting effects and secondary bacterial infections, it is essential to:

- Identify clinical signs early

- Carry out a thorough clinical examination (including the use of a rebreathing bag)

- Use upper and lower respiratory tract endoscopy to get an accurate diagnosis.

- Heather Busby