Resistance to equine parasite drenches is increasing, within New Zealand and worldwide, with up to 70% of equine properties in New Zealand now having some degree of drench resistance.

Currently, the drench families are:

Macrocyclic lactones (MLs) - these are the ones that end in -ectin (ivermectin, abamectin, moxidectin);

Benzimidazoles (BZs) - these end in -endazole (fenbendazole, oxfendazole);

Tetrahydropyrimidines - Pyrantel is the only drug in this family that we use in horses;

Praziquantel - for tapeworm.

Most of the drenches in New Zealand are combination drenches, and a lot of them include praziquantel for tapeworm.

Blanket drenching all horses at regular intervals is no longer advised because this tends to increase drench resistance.

Drench resistance develops because there will always be some random genetic mutations in parasites, meaning that some of them will naturally be resistant to certain drenches.

Then we inadvertently apply selection pressure by deworming the horse and killing all the susceptible worms. The mutant worms that are resistant will survive, and they are the ones that go on to reproduce. So, the more we drench, the more we select for resistance.

This issue is made worse when we underdose by giving the worms too small an amount of the drug. They are more likely to survive the underdose, develop resistance, and then go on to reproduce.

Something we need to remember is that all drugs within a drench family have the same overall mechanism. So, if you have a parasite that becomes resistant to one specific drug, it can also have the genes to be resistant to other drugs in that family.

The current situation is that ascarids are resistant to the MLs (-ectin) and there have been reports of resistance emerging to the BZs and pyrantel. Pinworms are also resistant to the MLs.

Small strongyles are resistant to the BZs and pyrantel, and resistance to the MLs is emerging. This is especially concerning, as typically our go-to treatment for encysted small strongyles has been moxidectin, an ML.

The scary thing about this is that there are no new drench families in development.

What will we do when the drenches stop working?

Developing a risk-based deworming programme is important for all equine property owners.

This starts with faecal egg count (FEC) testing before any treatment, to check for the presence of adult worms in all the horses’ faeces. This will establish which horses are contributing the most to the parasite contamination of the pasture.

All horses will have some worms, all of the time. However, 20% of the horses grazing a pasture will produce 80% of the worm eggs that are contaminating that pasture. A risk-based deworming programme will only treat the high-shedding adult horses.

In a risk-based deworming programme, the no-shedding or low-shedding adult horses may not need drenching, because they are not contributing to pasture contamination, and are also maintaining populations of susceptible worms.

We want to keep these populations of susceptible worms because it will minimise the increase of drench resistance in overall worm populations.

A risk-based deworming programme will take into account the number of horses you have grazing, what age they are, and what paddock management strategies you follow.

The types of worms that will be picked up in a FEC are the ascarids, large and small strongyles (not the encysted stage), and threadworms (in young foals).

It is important to note that the magnitude of the FEC is not equal to the magnitude of the actual worm burden within the horse, as most of these worms produce thousands of eggs per day. It is instead reflective of how much that horse is contributing to contamination of the pasture with parasite eggs.

A horse with a high faecal egg count is contributing more to pasture contamination than a horse with a low faecal egg count. The more parasite eggs deposited on the pasture, the more likely that a horse grazing that pasture will be infected (or re-infected) with parasites.

FEC and drench recommendations:

Foals:

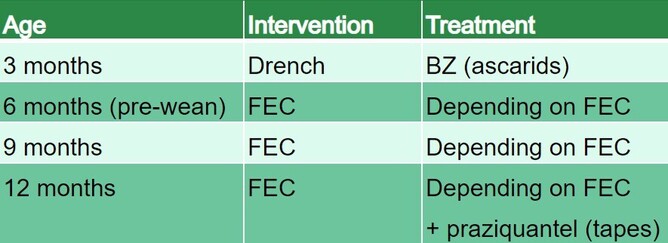

In general, it is recommended to give four drench treatments in the first 12 months. The first drench should contain a BZ for ascarids. Subsequent drenches will be decided upon depending on which type of parasites are present when a FEC is performed.

One of the last two drenches given to older foals should include praziquantel for tapeworms.

*Note that you should not use moxidectin in foals less than four months old due to an increased risk of toxicity.

Below is an example of a programme for foals, however this should be tailored to the specific grazing conditions on your farm.

Young horses (1-4 years):

As young horses are often high shedders, it is recommended to perform a FEC test four times a year (every three months) and drench appropriately based on the results of the FEC test.

Adult horses (>5 years):

Adult horses, including pregnant mares, should be FEC tested every three months, but only treat the high shedders (remember the 80/20 rule).

Geriatric horses:

Geriatric horses’ immunity to internal parasites can wane in their late teens, which means they can become high shedders.

They may also have comorbidities and other health issues such as PPID (Cushings), which further contributes to immunosuppression.

Guidelines for older horses are the same as for adult horses, with regular FEC testing being recommended.

The benefits of testing

Initially, FEC testing may seem like an increase in cost. However, the overall cost of parasite management may go down, as you will no longer be drenching all your horses, all the time.

Instead, you will just be drenching the horses that need drenching, and only at the exact times they need to be drenched.

FEC tests are a simple process. All that is required is for the horse owner to collect samples of the horse’s faeces (faecal balls) and seal them in an airtight zip lock bag. Then bring them into the clinic as soon as possible, within 12 hours is best.

Changes in paddock management and grazing strategies may also help to keep pasture contamination levels down, further reducing the need to drench all horses all the time.

Paddock management strategies which can improve parasite control include:

Low stocking density;

Picking up poo - twice weekly has been shown to have a dramatic effect on decreasing the risk of parasitism;

Cross-grazing (specifically with ruminants as they only share one parasite of low significance with equines);

Avoid using the same paddocks year after year.

Factors which can increase the risk of parasitism include:

High stocking density;

Harrowing – this spreads worm eggs/larvae over all the grazed area;

Grazing foals/young horses in the same paddocks each year.

By following a risk-based deworming programme, you can minimise parasites in your equine friends, thereby reducing the associated health risks.

Following a good programme will also contribute to slowing down drench resistance issues, until new solutions can be found.